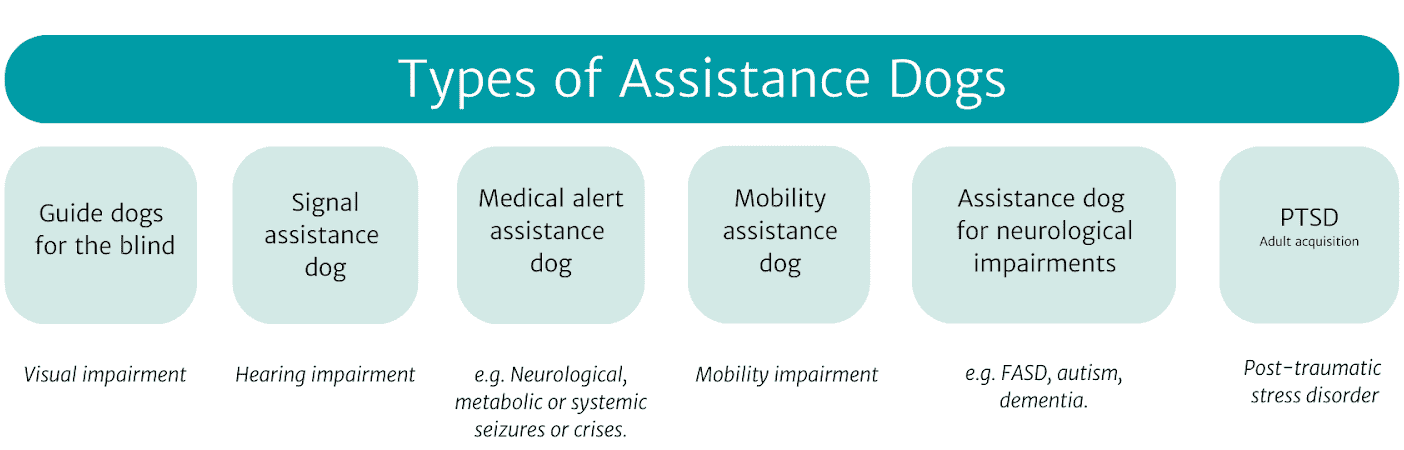

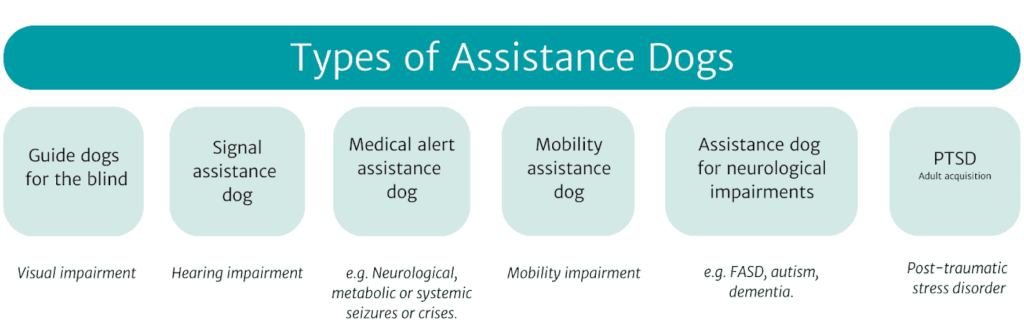

Types of Assistance Dogs1

Assistance dogs and psychiatric disabilities

Assistance dogs for individuals with psychiatric impairments are a recent concept that is growing rapidly in popularity. Recognizing the unique challenges presented by psychiatric impairments, Assistance Dog Foundation considers it critical to approach this topic with consideration and care. Just as each disability is unique, psychiatric disabilities also introduce complexities that are distinct from other forms of impairments. Handlers and assistance dogs can face challenges that lead to detrimental consequences. More – and more comprehensive, long-term – research is needed to establish appropriate frameworks – whether these impairments are the main or a secondary disability of the handler.

The act of living with a dog is not, by default, good for humans. Research2 has shown that such outcomes depend on the individual situation and context (i.e., Herzog 2011; Gravrok et al. 2019)3. Human-dog partnerships can be greatly rewarding if they are well-balanced, based on mutual care and respect, the handler has the appropriate material and immaterial resources to provide for the dog at all times, and both individuals can mutually benefit. However, if the challenges of successfully living and working together become unmanageable and/or detrimental for either human or dog, living with a dog can worsen the health and well-being of an individual, rather than solely improve it.

For this reason, an assistance dog is not always the right choice, no matter how much an individual may desire or need a solution. A failed partnership with an assistance dog can further amplify existing challenges instead of mitigating them.

For this reason, the fact that assistance dogs have been found to successfully mitigate disabilities for many, does not mean that they are always the right intervention for every individual. Good intentions are not the key indicator that a partnership will indeed be successful and produce the desired benefits for both human and dog.

Assistance Dog Foundation is challenging a tradition that treats assistance dogs as tools and the handlers as passive recipients of the dogs’ assistance. Instead, A-fdn’s view of the concept celebrates the handler and dog as partners in a dynamic, secure partnership, in which the handler plays a pivotal role. These human-dog-partnerships are complex and intricate, with the handler assuming multiple roles and responsibilities.

Despite their accommodating nature, dogs require confident and consistent guidance at all times and a predictable human partner: A handler who they can rely on to meet or exceed their needs in all Five Domains of Animal Welfare. This is particularly true for assistance dogs, whose work requires them to manage more stress on a regular basis than a companion dog.

A wide range of voices from within the community – handlers, professionals, and researchers – advocate for a more holistic approach when evaluating if an assistance dog can indeed be a viable, long-term solution for someone with psychiatric disabilities. This concern is valid both when the mental health issue is the primary disability, and when it is a comorbidity, an additional impairment. Increasingly, studies are considering both the welfare of the dog and the handler. After many detailed conversations with a wide spectrum of stakeholders, the Assistance Dog Foundation sees reason to apply caution in the certification of psychiatric or the newly appearing “psycho-social assistance dog” teams.

As an institution working according to international standards, the Assistance Dog Foundation certifies the qualification of the handler to lead the team throughout its existence – typically a period of 8 to 10 years. Certification thereby extends far beyond passing the Public Access Test. A-fdn’s Public Access Test is simply the beginning of a long relationship between the team and A-fdn. As a certifying body, it is our obligation to assure that the handler, with the highest likelihood, can maintain the certified level of competence and team partnership.

We are required to respond to concerns regarding the assistance dog team throughout their active partnership, and to withdraw certifications, when things do not develop properly.

For this reason, A-fdn is currently only cautiously admitting assistance dog handlers with psychiatric impairments to the Public Access Test. In response to comprehensive, long-term academic research or clear frameworks on the topic from reputable institutions in the sector, A-fdn will evaluate and adapt its policies.

A-fdn is not currently examining any emotional support animals (ESAs). Due to the unclear definitions in the sector, these are sometimes merged with the category of assistance dogs, for example when the “assistance dog for psychosocial impairments” was written into law in Germany. Internationally, ESAs are typically not considered assistance dogs.

Currently, the only psychiatric disability A-fdn admits to the Public Access Test is a clearly diagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), confirmed by a specialist, involving an A1 criterion according to the DSM4 and acquired during adulthood. Alternatively, diagnosis may also be provided by the employers’ liability insurance, the statutory accident insurance fund, or other agencies evaluating the case before assuming long-term responsibility.

PTSD acquired during adulthood

Various large studies exist on the benefits and risks of providing assistance dogs to individuals traumatized during adulthood. Most of these studies focus on military PTSD, suggesting frameworks that increase changes for long-term success. Such studies have influenced the prerequisites and competencies defined for qualified handlers, listed in Chapter B, giving us an initial framework to go by.

There is a significant gap in existing literature concerning comprehensive, long-term studies on pairing assistance dogs with people developing PTSD during childhood or adolescence. Existing trauma-related research5 suggests a cautious approach until further standards or frameworks have been established that support long-term success.

Footnotes

- Where an assistance dog is trained for more than one impairment, it is classified in its main category. ↩︎

- See our extensive bibliography at www.assistancedogfoundation.org/biblio ↩︎

- Herzog, Harold. 2011. ‘The Impact of Pets on Human Health and Psychological Well-Being: Fact, Fiction, or Hypothesis?’ Current Directions in Psychological Science 20 (4): 236–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411415220.

Gravrok, Jennifer, Dan Bendrups, Tiffani Howell, and Pauleen Bennett. 2019. ‘Beyond the Benefits of Assistance Dogs: Exploring Challenges Experienced by First-Time Handlers’. Animals 9 (203): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9050203.

↩︎ - “(…) direct personal experience of an event that involves actual or threatened death or serious injury, or other threat to one’s physical integrity; or witnessing an event that involves death, injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of another person; or learning about unexpected or violent death, serious harm, or threat of death or injury experienced by a family member or other close associate (Criterion A1), ESTSS, quoted on August 1, 2024. ↩︎

- E.g., in Eckstein, Sophia Dominique: Traumafolgen und Traumafolgestörungen bei Kindern und Jugendlichen nach psychischen Belastungsereignissen. 2013 and Van der Kolk, BA: Entwicklungstraumastörung: Auf dem Weg zu einer rationalen Diagnose für Kinder mit komplexer Traumageschichte. Psychiatrische Annalen, 35, 401-408. 2005). ↩︎